Highlighted objects

Marking 70 Years since the Passing of Esther Sephiha, née Eskenazi

It was in 1892 that Esther Eskenazi was born into a Sephardic family in Istanbul, in what was then the Ottoman Empire. Her family moved to Belgium in 1910. After her marriage to David Nissim in 1914, the couple moved to Brussels where they opened a carpet repair workshop a few years later.

The Sephiha family were practicing Jews. After the German occupation of Belgium, their Turkish citizenship initially exempted them from the mass deportations of Jews. Then in October 1943, after Turkey failed to repatriate its Jewish citizens before the deadline set by the Germans, which had been repeatedly extended, some sixty Turkish Jews in Belgium were rounded up by the SS and Gestapo. Those arrested in Belgium included David Nissim and Esther Sephiha as well as three of their six children, along with various relatives. On 13 December 1943, the women and children were deported to Ravensbrück Concentration Camp, where most were housed in Block 11 and assigned to the sewing workshop.

For more than fourteen months, the women were subject to the SS reign of terror and brutality. Seven of these women met their deaths in Ravensbrück. But Esther Sephiha and her daughters Germaine and Adele survived, having been sent to Istanbul on 28 February as part of a civilian prisoner exchange between Germany and Turkey. It was only in late 1945 that Esther Sephiha and her daughters were able to return to Brussels. She died on 22 July 1950.

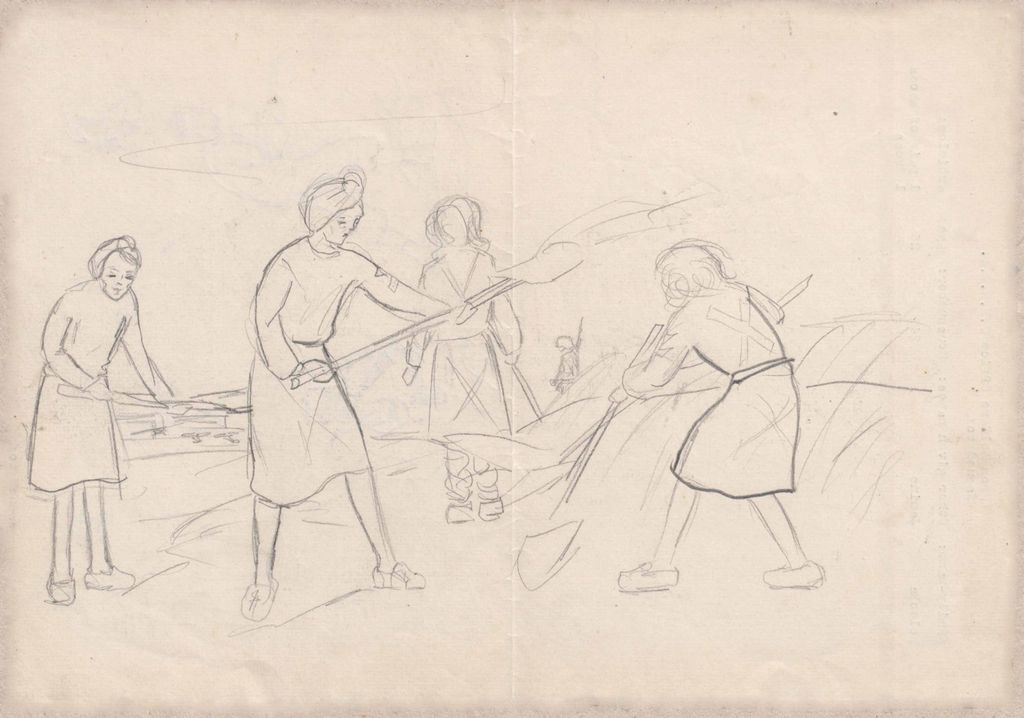

Drawing by Krystyna Zaorska

At the age of 14, Krystyna Zaorska was arrested with her mother Henryka in the raids

after the Warsaw Uprising in 1944. She arrived at Ravensbrück concentration camp in

October 1944 on a special transport from Warsaw. She was separated from her mother,

who was sent to the Königsberg/Neumark satellite camp. Krystyna Zaorska was allocated

prisoner number 76,933. She became seriously ill and was cared for by Polish prisoners.

She lived in Block 20 with other young people who did not have to work. In February 1945

her mother arrived at Ravensbrück. They were transferred together to Vennebeck/Porta

Westfalica, where her mother died of the after-effects of her imprisonment.

After her liberation by the US Army, Krystyna Zaorska stayed in the parachute settlement

in Emmerich. She finally returned to Gdynia, where she still lives, in 1946. She studied at

the University of Fine Arts in Gdańsk, specialising in sculpture and ceramics. In 1955 she

married Tytus Burczyk, a musician. The couple have three children and five grandchildren.

Today she still gives talks to younger generations as a witness of the Nazi period.

Many of her drawings are presented in the exhibition "The Ravensbrück Women's Concentration Camp. History and memory".

Photo of the Men’s Camp at Ravensbrück

This photograph shows the men’s camp at Ravensbrück, which consisted of five dormitory barracks and one utility building. In the background is the women’s camp along with its industrial yard. Separated from the women’s camp by a fence, the men’s camp saw more than twenty thousand inmates from 1941 to 1945. Most of them came from Poland, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Austria. They were often brought to Ravensbrück from other concentration camps.

The men’s camp was established by the SS in April 1941. Its inmates were to supply the labour needed for the expansion of Ravensbrück Concentration Camp, which was continually growing. Several rows of barracks, as well as the industrial yard, were added to the women’s camp. The male inmates also did clearance, drainage, and levelling work at the site of the Uckermark ‘juvenile protective custody camp’, in addition to constructing the Siemens factory buildings, carrying out expansion work at the SS housing settlement, and building roads. The majority of work details were for manual labour with civilian construction companies.

Most of the men were registered as political prisoners, aged 16 to 45. As for Soviet, Polish, and French prisoners, a large (but difficult to determine) proportion of them were forced labourers who had been put in concentration camps due to various ‘offences’ (such as sabotage or escape attempts). . Within the first year and a half of the men’s camp, nearly half of all inmates died from the consequences of overwork or through arbitrary killings.

This photograph was purchased by the Ravensbrück Memorial Museum in January 2020. It is still the only known photo of the five barracks forming the men’s camp.

Cölestine Hübner’s Travel Guitar

After a year of restoration work, the guitar owned by the late Cölestine Hübner is once again on display in the Memorial’s permanent exhibition.

The guitar was owned by Cölestine Hübner, an Austrian woman who worked as a singer in Vienna’s wine taverns before her arrest. She was allowed to take along her guitar to the camp, but had to play and sing for the SS during their ‘Viennese Evenings’. She also performed as one half of ‘Tini and Mimi’, a duo she formed with Hermine Freiberger, another Austrian inmate at Ravensbrück.

At some point, the guitar was treated with a modern varnish, probably in order to stabilise or cover the cracks that were already showing back then. Donated to the Memorial in 2011, the guitar went on display in 2013, placed in a climate-controlled vitrine.

With the support of Ravensbrück’s International Friends Association (IFK e.V.), which organised a benefit in order to raise funds for this purpose, the guitar’s restoration was begun in 2018. But first, a plan of action had to be worked out for the restoration effort. The Memorial decided upon a passive conservation strategy.

It was the guitar maker and restorer Philipp Neumann (of Leipzig and Antwerp) who was entrusted with the restoration. This included the installation of small blocks to stabilise the cracks in the soundboard, and reglueing the loose sides around the backboard’s bracing.

An analysis of the surface treatment showed that the modern coating was an alkyd resin varnish, one that could be stripped from the original shellac without harm. The cleaned surface was then given a coat of beeswax. Originally built by Johann Anton Stauffer in Vienna around 1843–48, this guitar is back on display in Room 4, which is dedicated to ‘Solidarity and Self-Preservation’

Guestbook from Ravensbrück’s Austrian Survivors

On the occasion of the first international meeting of ‘Ravensbrück women’, which took place in Fürstenberg on 10 September 1949, some Austrian survivors brought along a highly ornate guestbook, bound in brown leather. Women from all over Europe entered their names onto its pages, some with their addresses and former prisoner numbers. They did this on Fürstenberg’s market square, thereby endorsing the ‘Manifesto of the Women of Ravensbrück’ as set out on the first two pages. They vowed to dedicate all their energy towards building a new world of peace and democratic development, and to fight tirelessly against war.

The entries include the names of Erika Buchmann, Astrid Blumensaadt-Pedersen, Martha Desrumaux, and Edith Sparmann. These are the names of surviving eyewitnesses who, over the years, willingly entered the public spotlight, recounted their experiences, and/or published their writings.

Erna Lugebiel’s Miniature Slippers

Erna Lugebiel was born as Erna Voley in Berlin on 24 August 1898. Working as a dressmaker since 1920, she eventually became friends with the owners of her workplace, as well as other Jewish company heads and colleagues in Berlin’s garment industry. It was in 1933 that Erna Lugebiel began helping her Jewish friends and other victims of persecution by offering them refuge in her home, while also arranging for food, clothing, and other hiding places.

With the launch of the war, Lugebiel was drafted into the Wehrmacht as a telephone operator. In the early 1940s, she came into contact with the ‘Kampfbund’ resistance group and assisted the persecuted with money and accommodations. The Gestapo arrested Lugebiel in July 1943. She was charged in court with ‘preparing high treason, aiding the enemy, and undermining military morale’. Acquitted due to lack of evidence, she was then transferred to Ravensbrück Concentration Camp in November 1944 as a ‘protective custody’ prisoner. There, she became a ‘room chief’ in Block 7 of the infirmary zone. Following the Allied liberation, she stayed in Ravensbrück until late May 1945.

After 1945, Erna Lugebiel maintained close contact with other Ravensbrück survivors in West Berlin, as well as East and West Germany. She died in Berlin on 17 December 1984. In August 2019, Erna Lugebiel would have turned 111 years old.

These miniature slippers from Lugebiel’s estate were given to the Ravensbrück Memorial Museum in 1994 by her daughter Ingrid Rabe. As part of the permanent exhibition, they are on the upper floor in the room devoted to culture in the camp.

Guard Book for the Work Details of 1939/40

‘As punishment, I now had to do the hardest outdoor work. We moved furniture, shovelled sand, unloaded boats, and pushed wagons, with almost constant hunger. After a few weeks, I was transferred to the laundry room for further correction. Now I had to scrub sacks, as well as blood-covered sheets from the men’s camp, inmate dresses and uniforms. For months, I stood in the water from morning to evening.’ (Clara Rupp, MGR/SBG SlgBu vol. 35, report 657, p. 6)

As soon as the women’s concentration camp opened, its inmates also had to start doing forced labour outside the camp as well. To this end, work details were formed every day. A surviving guard book documents the various types of work performed by these women, ranging from lighter activities (cleaning, office duties), to gardening and agricultural tasks (at the chicken farm, at the manor estate), to the heaviest labours, which were also imposed as punishment (constructing roads, shovelling sand, unloading stones).

The SS guard at the camp’s gate used this book to record each work detail with date, number of women exiting and returning, time in and out, and the name of the responsible (female) overseer.

For the period from 3 October 1939 to 9 May 1940, a total of 3,605 work details are registered in the guard book, with seven of them crossed out. There are forty entries noting regular inspections by high-ranking SS officers from the camp’s administration up to 14 February 1940.

This guard book can be viewed as a PDF file at the Ravensbrück Memorial Museum’s archive. To facilitate study, there is also an Excel file.

Ceija Stojka’s Childhood Skirt

Born 1933 in the Austrian state of Styria, Ceija Stojka was arrested as a Roma along with her mother and siblings in 1943 and deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp. Its so-called ‘gypsy camp’ was broken up in August 1944, with ‘fit for work’ men and women transferred to other camps. Some one thousand women and girls were brought to Ravensbrück, including Ceija Stojka and her mother Sidi. Ceija Stojka, now 11 years old, had been passed off as a 16-year-old by her mother to get through the selection process in Auschwitz, since prisoners capable of work had better survival chances. Her work assignments at Ravensbrück included the sewing workshop.

In 1945, Ceija and her mother were deported to Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp. They were among the survivors liberated by British troops in April 1945. The two returned to Austria. With her 1988 book Wir Leben im Verborgenen [‘We live in hiding’], Ceija Stojka greatly raised awareness of the persecution suffered by Roma and Sinti under Nazism. She also began to reflect on her life experiences through artwork, putting her memories to paper by creating highly expressive images that favoured bold colours.

This skirt with appliquéd cross was worn in Ravensbrück by Ceija Stojka. It was in 1968 that she gave it to the Ravensbrück Memorial Museum, which she then visited frequently in the 1990s. Ceija Stojka died in Vienna in January 2013.

Unearthed: Food Pail

This pail was used for transporting meals from the inmates’ kitchen to their respective blocks. Such pails often contained soup and could weigh up to fifty kilograms when full. Its two handles allowed the pail to be carried by a pair of inmates, who were often weakened and malnourished. In the 1950s, Else Schöpke described how in her early weeks of imprisonment as a ‘political prisoner’ at Ravensbrück she had to ‘haul heavy food pails from the kitchen to the block every day for some 1,600 inmates’.

During the first two years of the women’s camp, the food situation was still tolerable. But it started getting worse and worse from 1941. By 1944, the women’s camp inmates were down to 200 grams of bread per day, along with a cup of imitation coffee in the morning and half a litre of thin vegetable soup at lunch and dinner. In the winter of 1944/45, the daily rations often consisted of just 100 grams of bread and one bowl of soup made from potato peels or beet-processing waste. There was a constant struggle for food in the camp. The prisoners were malnourished and many died from the terrible shortages.

Hunger, meal times, and the transport of food in pails are common motifs in the artwork created by former inmates. Good examples are the drawings of Nina Jirsiková, Violette Lecoq, and Jeanne Letourneau, on display in the Ravensbrück Memorial Museum’s main exhibition.

The food pail was discovered during works done near the waterworks building in 2018, and will be exhibited in the visitor centre’s display case from April 2019.

Magdalena Herskovitz’s Childhood Hat

Magdalena Herskovitz’s first years of life were spent in hiding in Slovakia. In this satellite state of the German Reich, the systematic persecution of the Jewish populace began in 1942. Magdalena Herskovitz’s family tried to evade their oppressors, but were betrayed. In December 1944, the three-year-old was sent to Ravensbrück Concentration Camp alongside her mother and sister. She died there on 8 March 1945. Her hat was donated to the Memorial in 2007 by her sister Eva Bäckerová.

Ravensbrück’s inmates included at least nine hundred girls and boys between the ages of two and sixteen, from eighteen nations. They were admitted with their families or were transferred from other camps without relatives. Around 560 children were born at Ravensbrück Concentration Camp between 1943 and 1945. Most newborns died after a short time.

Boys were usually placed in the men’s camp from the age of twelve, getting their own block there in the autumn of 1944. In the women’s camp, the children stayed amongst the adults. They began working around the age of twelve, with younger ones remaining in barracks during the day. Fellow inmates secretly arranged for toys and lessons, while ‘camp mothers’ looked after children without family. The children’s games, such as ‘roll call’, ‘selection’, and ‘SS’, were based on camp life.

Magdalena Herskovitz’s childhood hat is shown in the main exhibition at the Ravensbrück Memorial Museum. It is one of two objects highlighting the fate of Czechoslovakian inmates (upper floor of SS Headquarters, Room 2.2).

The Prisoner Number of Yevgenia Klemm (née Radakovic)

Yevgenia Lasarevna Radakovic was born in Belgrade on 20 December 1898. After graduating university, she went to Odessa and taught history in schools, as well as the methodology of teaching history at the Pedagogical Institute. In October 1941, she volunteered to serve as a nurse on the war front. Falling into German hands as a prisoner of war in 1942, she was ultimately transferred to Ravensbrück Concentration Camp. At the camp, Yevgenia Klemm secretly taught German and history to her fellow inmates.

While on an evacuation march in April 1945, she was liberated by the Red Army. In the autumn, she returned to the Pedagogical Institute in Odessa. But she was later suspected of having collaborated with the Germans while in captivity, resulting in her dismissal. She subsequently committed suicide that same year, on 2 September 1953. In her farewell note, she wrote: ‘I have always believed that to work means to live and to fight. Not working means not living.’

Yevgenia Klemm’s prisoner number was given out in the spring of 1943. This enables a rough approximation of when she arrived at Ravensbrück Concentration Camp. The object came into the collection in 2011 through the mediation of journalist Sarah Helm, and is currently in the Ravensbrück Memorial Museum’s depository.

Drawing by Nina Jirsíková

The undated drawing Nocní setkání (‘nocturnal meeting’) is one of the few cartoons made by the Czech Nina Jirsíková (1910–78) during her camp internment. It depicts a secret meeting between the bathing room and latrines.

Nina Jirsíková was a dancer, choreographer, and costume designer. Starting at the age of 16, she worked at places like the avant-garde Theatre D-41 (‘Decko’) in Prague. She was arrested on 12 March 1941. The trigger was a performance of the ballet Pohádka o tanci (‘The fairy tale of dance’), which was seen as a parable about the Nazi occupation.

Nina Jirsíková was taken to Pankrác Prison in Prague, and then deported to Ravensbrück Concentration Camp in late 1941. She was given the prisoner number 8681. Her forced-labour assignments included the camp’s fur-processing and textile-shredding workshops, and then later at the nearby Siemens workshops. In her few hours of ‘free time’ in the block, she danced, drew satirical drawings, and even wrote a comedy. Such activities were against camp regulations, and could result in cell block detention or flogging.

After her liberation, Nina Jirsíková worked in theatre again, but could no longer dance due to physical ailments. In 1972, she wrote her account of ‘artistic activities at Ravensbrück Concentration Camp’. She died on 23 November 1978.

This drawing and others by her can be seen in the permanent exhibition The Ravensbrück Women’s Concentration Camp – History and Memory

Isa Vermehren

The memoirs of Isa Vermehren are among the earliest published eyewitness accounts. The first edition was published by Christian Wegner Verlag (Hamburg 1946) with the title A Journey through the Final Act: A Report (10.02.44 to 29.06.45). Numerous editions of Vermehren’s book have been published since then, most recently by Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag (Reinbek bei Hamburg 2005).

The author was born in 1918 in Lübeck. Her opposition to the Nazi regime prompted her to leave school in 1933. She subsequently moved to Berlin. From 1933 to 1935 she performed at the Katakombe political cabaret in Berlin. When the cabaret closed, she completed her school-leaving exam. In 1938 she converted to Catholicism. Her family was arrested in 1944 in retaliation for Isa Vermehren’s brother having requested political asylum overseas. Isa Vermehren was first sent to the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp and then to other prisons and camps.

In Journey through the Final Act, she describes her imprisonment in Ravensbrück and elsewhere until she was liberated and returned home to Hamburg. In 1947 she appeared in the film In Those Days directed by Helmut Käutner. She played the role of the maid Erna, who tries to help the mother of one of the assassins of 20 July 1944 go into hiding.

Isa Vermehren earned a degree in languages, became a nun in 1951, and worked as a headmistress in Bonn and Hamburg. She died in 2009 at the age of 91.

After the fall of the inner-German border, Isa Vermehren visited the Ravensbrück Memorial to give a reading. On the 50th anniversary of the liberation of the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp she visited the Memorial again to take part in an ecumenical service. In 1994, she sat for a portrait by the painter Christoph Wetzel from Dresden.

There is an interview with Isa Vermehren in the video archive 'The Women of Ravensbrück' by the director Loretta Walz.